Curiously both these events serve to highlight one important underlying reality - Czech voters are deeply dissatisfied and in a highly skeptical mood, since following seven quarters without growth the country's economy is evidently stuck in the doldrums. The worst part is things look highly unlikely to improve anytime soon.

Naturally the flood damage has resurected an old and somewhat tiresome debate about whether or not destruction is actually good for an economy. The last time this surfaced in any significant way was in the aftermath of the Japanese tsunami (see my piece of the time here), and as we can now see all that reconstruction spending totally failed to get the economy back on track, although it did leave the ailing country with just a bit more debt.

As I think everyone agrees, flood damage is a form of wealth destruction. If you have a house on one day, and the next you don't then somehow you feel poorer. It isn't really surprising that you feel poorer because in actual fact you are poorer. Naturally, if your home gets rebuilt, and you find yourself with an even better one as a result, then you may even feel you have benefited (although what about all those valued personal belongings you lost), but that will be because someone else, either a government or an insurance company, has made good your loss, so they are poorer instead of you. As Reuter's reporter Michael Winfrey puts it: "Governments and insurers from Germany to Romania will have to pick up the costs of helping families and business recover from the floods, which have killed at least a dozen people and driven hundreds of thousands from their homes since the start of June".

Now clearly in the short term GDP may benefit, since spending money will generate economic activity. As the country's Finance Minister Miroslav Kalosuek told Czech Television at the time: "If we take just the normal households, and how many brooms, bleach and rubber gloves they must suddenly buy, that is demand. There will also be demand in construction, demand in renewing roads, higher demand for certain goods and services. And higher demand is pro-growth."

But will the extra demand really generate extra growth in the longer run, rather than simply advancing spending from the future to now (or as the Spanish expression so evocatively puts it "give us bread for today and hunger for tomorrow") ? The evidence we have seems to suggest that it will if the problem the economy was suffering from was a lack of stimulus - which brings us nicely round in a circle to the stimulus versus austerity debate. But if lack of stimulus wasn't the problem, as we have seen in the Japan case, an extra reconstruction programme won't make a blind bit of difference at the end of the day. It will simply shift demand around a bit in time.

So which is it? Is the Czech Republic suffering from a normal common or garden recession, one in which a bit more stimulus might help, or is something deeper going on?

The Demographic Spanner Stuck In The Works

The Baltics, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria are all recognized - each in their own way - to have encountered serious economic problems and generated sizable imbalances during the run in to the global financial crisis. These problems - at the time - were seen as placing serious question marks over the underlying soundness of a group of economies which in the pre-2008 world were often lauded for their growth prowess and fiscal abstemience when compared with their West European neighbors. The fact that these countries started, one after another, to go off the rails could be explained by viewing them as examples of the "weaker economic cases"in the group.

But when, in a way which curiously parallels what is now happening in purportedly "core Europe" countries like Finland and the Netherlands in the West, what were previously regarded as best-case-scenarios, like the Czech Republic and Slovenia, start to struggle and then continue to flounder, well perhaps we should be raising more than an eyebrow or two - indeed, maybe we should really be asking ourselves some serious, thought-provoking questions not only about the structural depth of the problems being faced by the whole group of Eastern Accession countries, but also even about the very soundness and adequacy of the received theories the main multilateral policy institutions are working with.

In the current case, the Czech Republic is now in all probability in its eighth quarter of recession - and the last time the economy actually grew was in the three months up to June 2011. This is quite a preoccupying outcome for a country which was not perceived to be suffering from any special problems - like outsize credit booms, or government fiscal largesse - in the pre-crisis world. The economy is now moving sideways, and, more importantly, substantial question marks hover over what the country's real future growth potential actually is. Certainly, and in any event, it is well below that which was considered a norm pre 2008.

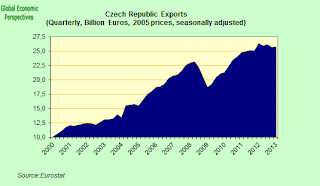

In the past the country was characterised by and renowned for the soundness of its industrial base and its strong export performance, but the continuing crisis in the Euro Area (the principal source of external demand for the country's products) has meant overseas sales have been largely stagnant for some quarters now. And with countries in Southern Europe striving to make a substantial competitiveness correction and claw back some of their lost ground, it is in the East of Europe where the impact of these efforts is likely to be most acutely felt. It was precisely during the time that the Southern economies were shifting over to credit-driven service ones that their Eastern counterparts were busy building their industrial foothold in the EU. Now those in the East face the risk that a sizeable chunk of this coupling and integration process may simply unwind. A rising tide may lift all boats, but what does a flat sea do?

Czech industrial activity has become virtually stagnant when it isn't actually falling.

And construction is steadily sliding downhill.

In addition to the loss of export leverage household consumption has remained very weak. As the IMF put it in their latest country report, "the export-led recovery observed in 2010-11 subsided as euro area import demand slowed, and growth has noticeably underperformed trade partners and peers since the middle of 2011 mainly because of weaker domestic consumption and investment."

Naturally, both the IMF and EU Commission assume that what is happening to the country does not go far beyond a short term blip, and both institutions take it as a given that "recovery" will set in somtime soon. As the IMF puts it, "The Czech Republic's economic fundamentals are strong." The EU Commission broadly agrees: "Due to a strong downturn in consumer confidence, a drop in public investment and a weaker external environment, real GDP is estimated to have decreased by 1.3% in 2012. As these factors ease off in 2013, economic activity is forecast to bottom out in the middle of the year. The recovery is expected to consolidate in 2014, supported by growth of real household income".

That being said a nuanced but interesting divergence has emerged between the two Troika partners over the immediate outlook for the country. While EU Commission see "domestic risks to the outlook" as "fairly balanced", the IMF feels general risks lie "mainly to the downside" highlighting the risks of "further deterioration of euro area growth" and the danger of "permanent scars to potential growth".

The Fund explain their concerns as follows: "With recent disappointing export performance, the economy is at the risk of being dragged deeper into recession. Also, the current poor growth performance, if protracted, runs the risk of translating itself into a long-term decline in potential growth due to lower investment." I.E. the slowdown could eventually become self perpetuating if the recession becomes an even more dragged out affair. Unfortunately this possibility is far from being excluded.

Given the existence of such risks it is worth asking ourselves whether growth in the Czech economy really will bounce back to an average of around 2.8% a year between 2015 and 2018? What is there in the works which really could make such a growth spurt - from the current near zero level - possible? Or could the IMF forecast numbers not be just another example of what Christine Lagarde once called “wishful thinking” of the kind that has been habitually practiced in, say, the Greek case.

But let's put the question another way. What might impede the country from reverting to a pattern of strong growth rather than simply continuing to bounce along the flatline? Well, you've got it - it's the demography stupid! The Czech Republics population and workforce just turned the historic corner pointing towards long term decline. To some this piece of information may seem surprising, but CEE demographics in general really are quite unique, since while fertility fell and life expectancy started to rise as it did in the West, due to the development delay produced by nearly half a century of communist government most of these countries are now in the process of getting old before they get rich, creating a very special set of economic growth and sustainability issues.

Czech fertility has long been below replacement level, and has been below the 1.5tfr level since the early 1990s.

The Czech population has been virtually stationary over the last few years, but is now finally starting to contract.

As in many countries on the European periphery the decline is an indirect by-product of the economic crisis. Population levels which were previously precariously balanced around the zero growth line are suddenly being destabilised by the drop in births associated with the recession and the sudden disappearance of the positive net number of migrants arriving which helped keep the balance in the pre-crisis world.

"In the first three months of 2013.... net international migration was equal to minus 4 people – the number of emigrants was 9 998 people and number of immigrants was 9 994 people. The highest net migration was reached with the citizens of Slovakia (1 213 people) and Germany (334 people), followed by United States (290 people) and Romania (213 people). The considerable decrease was registered in the number of citizens of Ukraine (by 2 201 persons), Czech Republic (by 505 persons) and the number of Vietnamese citizens (by 427 persons)".

But even more important (in terms of GDP growth potential) than the overall population decline (which is still tiny) is the fall in working age population (WAP). Following a pattern seen in country after country along the periphery, the start of the decline in this population group has also coincided in time with the onset of the European debt crisis.

This means that employment growth will have the wind blowing against it, rather than behind it, and that it will become harder and harder to get GDP growth from adding extra labour (indeed at some point the number of those employed may well become negative) and the only major impetus towards headline GDP growth will have to come from productivity improvements. For an examination of this issue from the Portuguese point of view see this post here.

Is There Deflation Risk?

One of the lesser known details about the Czech economy is that - since it has retained its own currency, the Koruna - it has its own independent monetary policy and the central bank therehave now been holding interest rates about as near zero to zero as you can get (0.05%) for the past 8 months. This puts the country's bank in more or less the same situation as most of its better known peers across the globe - namely it is now up against the "zero bound" which makes it difficult to lower nominal interest rates any further.

With inflation weakening the debate at the central bank is now moving towards whether it will be necessary to use exceptional measures of the kind which would elsewhere be called QE. One option which is under consideration is a local version of "Abenomics" whereby the bank actively intervenes in the currency markets to provoke Koruna weakening - not so much to generate more export competitivness (banned by the G20) but rather in order to to try and raise the price level and avoid deflation risk (see these comments from central bank board member Lubomir Lizal). Such interventions, which (as in the Japan case) target the price level and not the currency value are for the time being accepted by the international community.

At the present time the Czech Republic is experiencing strong disinflation rather than outright deflation, but the IMF clearly see a danger if domestic demand remains weak and the economy continues to drift that this could become outright deflation.

The policy interest rate has reached the zero bound, but risks to inflation are to the downside. The Czech National Bank (CNB) was swift to cut its policy rate by 70 basis points to 0.05 percent between June and November 2012. Inflation declined below the 2 percent target level starting from January 2013, as the effects of 2012 VAT hike subsided and contributions from food and fuel fell. Inflation is projected to remain at around 1¾ percent through 2014, but risks are to the downside in line with the risks to the growth outlook.and:

"If a persistent and large undershooting of the inflation target is in prospect, the CNB should employ additional tools. The CNB’s statement that additional monetary easing within the context of inflation targeting framework would come from foreign exchange (FX) interventions is welcome and has been clearly communicated. The mission agrees that FX interventions would be an effective and appropriate tool to address deflationary risks."The risk of outright deflation is thus intrinsically linked by the Fund to the downside risks to headline GDP growth. If the economy under-performs, and investment does not bounce back then not only will there be damage to the country's long term growth potential, movements in prices might turn negative.

Japan With A Current Account Deficit And Negative Net External Investment Position?

Few, I suppose, would have thought there would be any good reason to make a comparison between the Czech Republic and Japan. Naturally it is noticeable that both countries have strong industrial bases and are very dependent on exports for growth. But beyond that it would seem the two countries have little in common.

Except, except..... what about the decline in working age population (WAP)? Isn't that the factor that many feel is behind the ongoing battle that Japan is fighting with deflation? (See, for example, this post). The Bank of Japan has long recognised that there is some sort of correlation between the rate of workforce growth and the rate of inflation (see chart below), with price inflation turning negative at more or less the same time as labour force growth did. The causality behind the correlation would be connected with the rate of rise (or decline) in domestic demand (initially consumption and then investment). Movements in WAP could be considered to be a good proxy for movements in employment and incomes, and hence consumer demand. As a country's WAP enters decline then domestic demand tends to weaken and following this the investment which goes with such demand does not occur. This is why failure to adequately resolve the present malaise into which the Czech Republic has fallen could produce a long term negative consequence for trend growth, as the IMF have highlighted.

Thus it isn't just a coincidence that the Czech Republic is starting to notice a fall in domestic demand and a fall in investment at just the time when the working age population starts to decline. This is a development which needs to be closely watched.

But, beyond any loose similarities, there is one important sense in which the country differs from Japan - the state of its Net External Investment Position.

The Czech Republic has, as I have repeatedly stressed, a strong export sector. So much so that the goods trade balance tends to be positive and large. What's more, it has been growing rapidly since the crisis. In fact, in Japan as the population has aged this balance has weakened.

But while in Japan the current account balance remains strongly positive, in the CR it is constantly negative.

The reason for this apparent paradox lieswith the large negative income component in the current account.

This income component is largely made up of interest payments on external loans (for example in the banking sector between West European parent bank and Czech subsidiary) and dividends on equities owned by non residents (for instance non-Czech parent companies which bought into Czech utilities during the privatisation wave).

The income item is large and negative due to the country's strong negative Net International Investment Position. Simply put non Czech nationals have more investments in the Czech Republic than Czech citizens have abroad to the tune of some 50% of GDP. In an ageing society, with a shrinking workforce this situation is simply not sustainable. Czech companies and citizens need to save more, even though this will weaken domestic demand further and make the country even more dependent on exports, and more of these savings then need to be invested abroad to generate an income flow which will help the country support its rapidly ageing population from 2020 onwards. This situation is widespread across Eastern Europe (see Hungary here and Bulgaria here).

Summing up: In recent years Czech exports have performed remarkably well, and the country has a strong goods trade surplus. The problem is that most of the country’s exports have been geared to the European market, and consumption in this area is now stagnant with a tendency to decline. In addition the country is heavily indebted abroad. With each passing day the CR looks more and more like Germany and Japan, without the strong overseas investment stock which gives the economies of those countries some sort of stability. The country cannot gain enough export momentum and as a result the economy languishes in recession.

The thing about elderly economies is that they no longer stand on two pillars, domestic consumption steadily runs out of steam, and the economy becomes export dependent. This is what can be observed in the Czech Republic, and the country’s demographics make it unlikely we will ever see strong growth in private consumption again.

On the other hand the country has a low sovereign debt level – around 45% of GDP – and before the onset of the latest recession it did maintain a reasonably strict fiscal discipline, despite the fact that with an ageing population the costs of health care and pensions continue rising annually.

One of the reasons for the low sovereign debt level is the fact the country privatized a number of its state owned companies at the start of the century - and herein lies the problem on the income side of the current account. Privatising to overseas (rather than domestic) investors means the even though the sovereign itself is less indebted, the level of indebtedness of the country as a whole doesn't change much. Ultimately the sovereign supports the nation, and the nation the sovereign, so apart from the political debate about larger or smaller government the rest is more akin to moving the deckchairs around. This kind of privatisation does not guarantee long run sustainability for the country, and if not backed by a rise in domestic saving it can become "bread for today and hunger for tomorrow" as the Spanish expression goes.

So despite being out of the Euro, and having the ability to devalue, it is not clear to what extent the Czech government will be able to withstand popular pressure to increase spending in the face of a stagnant economy. Without some plan for handling the ageing population problem calls for continuing austerity will likely fall on increasingly deaf ears as they do in country after country along the EU periphery. Despite talk of a constitutional change limiting public debt to 50% of GDP, as we are now seeing in the Polish case such laws are easier to enact than they are to implement. So it is likely that the current wave of austerity policies will increasingly come into question if, as seems probable, the economy continues to stagnate. In which case watch out for credit rating downgrades, and future surges in yield spreads on the one hand and growing deficit and debt levels on the other. As Paul Krugman once put it, some countries have low growth because they have high debt, and others accumulate high debt because they have low growth. The latter is in dabger of becoming the Czech case.

.png)